Prior to the pandemic, I worked in my first co-op at Wayfair in Boston. Even though I was only a second-year college student at the time, my manager confidently handed me the project and let me take autonomous control. I made minor mistakes, but they all helped me to learn and grow. For that reason, I decided to find my second co-op also in the United States. However, my plan was disturbed by the pandemic outbreak in 2020, when I went back to my home in China. Therefore, I switched my focus and found an internship opportunity in Shanghai Media Group (SMG).

Having been abroad since I was 14, I was much integrated into the American way of doing things, despite the fact I grew up in China. I was informed of the differences and understand that the tolerance in general is high; nevertheless, this does not mean that I can proceed without prudence.

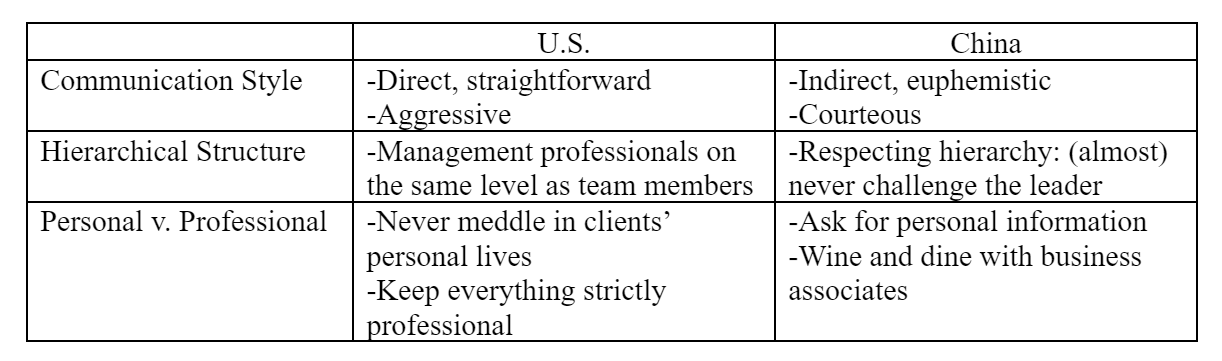

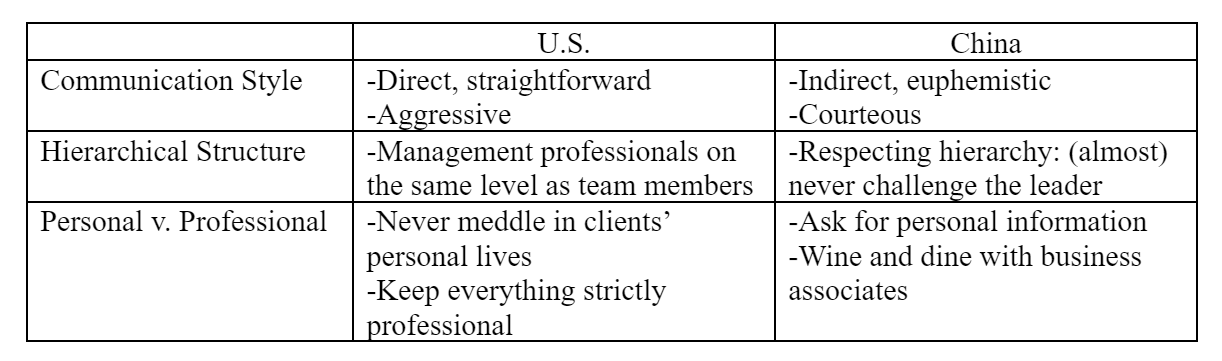

According to International Business Seminar (IBS), differences in business culture can create friction if not handled properly. In its article “Differences Between US and China Business Etiquette” (2018), the author points out several major distinctions, which I have organized in the table below.

Instead of offering advice, I intend to write about what I have seen and experienced at SMG, to give you a feeling of what it is like to work in a Chinese company. Please keep in mind that the differences listed in the table can only serve as a guide; differences do not mean inflexibility.

My team went out for shooting in the early morning for an entire week, and it was the coordinate party’s responsibility to provide breakfast. However, this was not stated in the contract, but more as a tacit agreement. The first days of shooting took place in companies, where they have dining halls for food. On the last day, we went to shoot in an alley. Our crew went straight to the site and did not have a chance to eat breakfast, but the manager from the coordinating party did not know. Instead of directly telling her about it, my manager complained in a plain tone that he was starving. The other manager immediately got the point, and she asked whether we had eaten and if we wanted her to order delivery.

Again, rather than agreeing without hesitation, my manager rejected, “it’s okay, I will order something later”. Regardless of his words, the manager from the other company ordered a group delivery for our crew. Even though both parties could speak explicitly, it is often expected for one party to express in a tactful manner and the other to understand the hidden message.

At the end of the year, my team began to wrap up and make summary presentations for stakeholders. During the team meeting, our head manager presented us with the PPT he designed. The PPT was informative, but one weak point was that there were too many words and not enough visual elements. When he asked for feedback, everyone complimented and only mentioned some minor problems, such as the numbers or change of a picture. I hesitated to point it out during the meeting, so I went to the head manager afterwards. My head manager appreciated my comment, and he acknowledged his lack of experience in making presentations. To my surprise, he told me that I could just speak up during the meeting, so everyone can hear my opinion. From his modesty, I understand that the practice is not to “never challenge the leader”, but to offer my thoughts in a sincere way. However, this is only applicable when we are having meetings in our own team; pointing out the “flaws” in front of a large group of people, especially important stakeholders, will be perceived as disrespectful and abrupt.

When I first joined my team, I was not asked to do a self-introduction. However, during spare time, such as at lunch break, my teammates casually asked about my background. My head manager asked me about my previous co-op in the U.S., and how much I was paid. My initial reaction was a little uncomfortable, especially when he asked me about my wage. However, I did not take the matter too seriously to my heart. The more I worked in the team, the more chances I had to have random chats with the head manager. It appeared that he used to go on business trips to the U.S. frequently, and I was the first of the few interns who go to a school in the U.S. It was not that he is interested in the wage per se, but he was more curious about the education and employment system in the U.S. To the Chinese, asking personal questions is to know the person, so they can build trust in the relationship. Still, one should maintain formality and talk in a respectful manner, not to mistake the questions as an invitation to be excessively familiar.